Wonders of the Roxburgh Gorge

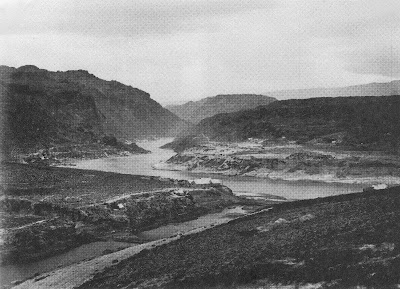

Before the Roxburgh dam was commissioned in 1956, the 30 km Roxburgh Gorge was up to 400 metres deep, and so narrow that in places its towering walls rose vertically above the boiling waters of the Clutha Mata-Au. The river was so constricted that it flowed as swiftly as 40 kilometres an hour through narrow chutes hundreds of metres long. In other sections the current slowed - but not much, flowing over landslide obstructions that had at one time dammed the gorge, before being overtopped by massive rapids. Today's sedate current bears no resemblance to the powerful torrent that once echoed through the gorge, drowning out the voices of men.

The first feature of the gorge, 675 metres below the Manuherikia confluence, was a constriction formed by schist bluffs on both sides that reduced the width to just 39 metres. This is now known as the "Italian Bend," but the early gold-miners called this the "Gates of the Gorge." Foot-tracks were etched precariously along the steep and boulder-tumbled walls of the gorge on both sides, as the miners hunted up gold and dug cave-like shelters under large slabs of fallen schist.

Just over five kilometres down the gorge from the "Gates," and nearly two kilometres beyond Butcher's Point, the true left wall of the gorge had long ago collapsed, blocking the river. The resulting over-topping waters had cut through the obstruction with unimaginable force, forming a torrential rapid that had over time, at its foot, scoured out a large, amphitheatre-like basin within high walls of unstable rock. This rapid, descending through a narrow chasm, was known as the "Golden Falls." It filled the "Narrows" with a crashing din so loud that shouting men could not hear each other. In the centre of this basin below the rapid, the deeply driving waters had pushed up a shingle island. Hence, the name "Island Basin." The Golden Falls and Island Basin were astonishing features in a remarkably dramatic location.

Beyond Island Basin at Doctor’s Point, two powerful rapids known as Doctor’s Falls No 1 & 2 dropped through a boulder strewn constriction below a maze of gold workings, stone cottages and cave shelters etched into the true-left side of the gorge.

Nearly two kilometres below Doctor's Point, the river again met a sudden obstruction. A huge schist slab had slid down from the true left into the river, against which river-borne shingle and boulders had jammed up, creating a rapid so tumultuous that the gold-miners called it the Molyneux Falls. Here was a ferocious whitewater descent, tumbling violently some four-metres down a twenty-metre section of boulders, at breathtaking speed. At normal or low flow, these falls were deadly. In high flow they were somewhat washed out, but still incredibly swift.

The gold-miners, dreaming of lowering the river above the falls to expose gold, tried several times to blast the huge thirty by twelve metre schist slab that lay at the head of the Molyneux Falls. But time and again the slab didn't move. Drilling and blasting merely succeeded in cracking the slab, so that it settled into place even more.

Further down the gorge, other rapids also raced through narrow chutes, until finally, at the southern end of the gorge, after boiling through massive eddies near McKenzie's Beach, the current eased slightly as it passed another bluff at Coal Creek - a site selected for the construction of the Roxburgh dam in 1947.

It is worth remembering that the wonderful features of the old Roxburgh Gorge were never physically destroyed prior to the filling of the Roxburgh reservoir. They were flooded, and now lie mothballed in silt. Given the limited lifespan of the ageing Roxburgh dam, and the silting, flooding and instability issues of the gorge, there is an ever-growing case for dam decommissioning and gorge restoration.

Inevitably, some time in the future, the largest high volume rapids in New Zealand - the once thunderous Golden and Molyneux Falls, will be re-born. Gradually, decades of trapped sediment will be stripped away, and the long-hidden wonders of the Roxburgh Gorge will be revealed.